Eugenics - An Overview Of The Practice Of Sterilizing Other Humans

From Ancient Punishments to Modern Bio-politics

Introduction

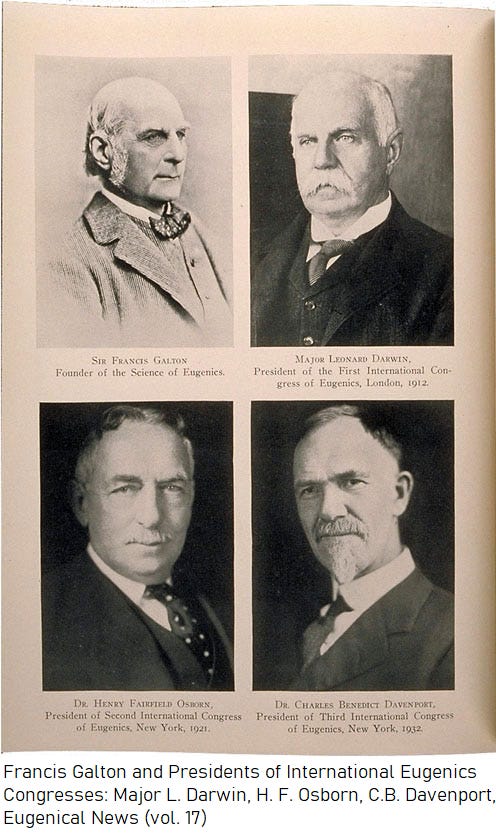

The history of human reproduction has long been entangled with questions of power, hierarchy, and social engineering. From the earliest punitive castrations of antiquity to the coercive sterilization laws of the early twentieth century, some sought to regulate who was permitted to reproduce and under what conditions. Although framed as a scientific pursuit aimed at improving the “quality” of populations, eugenics rested on profoundly flawed assumptions about heredity, race, intelligence, and social behavior. Its key actors - Francis Galton, John D. Rockefeller, Charles Davenport, Harry Laughlin; their heirs, via institutional networks supported by “philanthropic” founders - created an intellectual and bureaucratic apparatus that profoundly shaped public policy across the United States, Europe, and major parts of the world.

By the mid-twentieth century, the explicit language of eugenics had fallen into disrepute, particularly after the atrocities of the Nazi regime. Yet its core anxieties and objectives survived under new labels and within new institutional homes. Neo-Malthusianism reframed population control not as a matter of “racial hygiene,” but as a global imperative tied to economic development, environmental sustainability, and geopolitical stability. International organizations, philanthropic foundations, and national governments embraced family-planning programs - sometimes voluntary, often coercive - with the stated goal of reducing fertility in “high-growth” or “underdeveloped” populations. Much of this work relied on the same assumptions about who should reproduce, though expressed in the secular language of modernization theory, resource scarcity, and “responsible parenthood.”

Today, it is more important than ever to understand how these ideas evolved. The world is undergoing a rapid and unprecedented demographic shift: birthrates have fallen below replacement levels across most of the developed world, and even in many developing regions. The acceleration of this decline since the COVID-19 crisis - driven by economic uncertainty, social disruption, poorly tested experimental products,1 and long-term shifts in family formation - has reignited debates about fertility, state intervention, and the future of populations control. At the same time, biomedical science has entered a new era. Genetic-therapy-based vaccines, genomic editing technologies, and reproductive bio-technologies offer profound medical possibilities, but also reshape longstanding ethical dilemmas about bodily autonomy, consent, and state or institutional influence over reproduction.

Understanding the genealogy of eugenics - its intellectual origins, its institutional machinery, its global diffusion, and its modern re-branding - is not a historical exercise alone. It provides essential context for evaluating contemporary public-health strategies, demographic anxieties, and emerging genetic technologies. This article situates the evolution of eugenic thought within a broad chronological and global framework, tracing how ideas about “improving,” limiting, or directing human reproduction have adapted to changing scientific paradigms, political environments, and technological capacities.

In a world facing both drastically declining births and rapid advances in reproductive and genetic bio-medicine, revisiting this complex legacy is crucial for understanding how societies - past and present - construct the boundaries of reproductive autonomy, define “fitness,” and legitimize interventions into the most intimate aspects of human life.

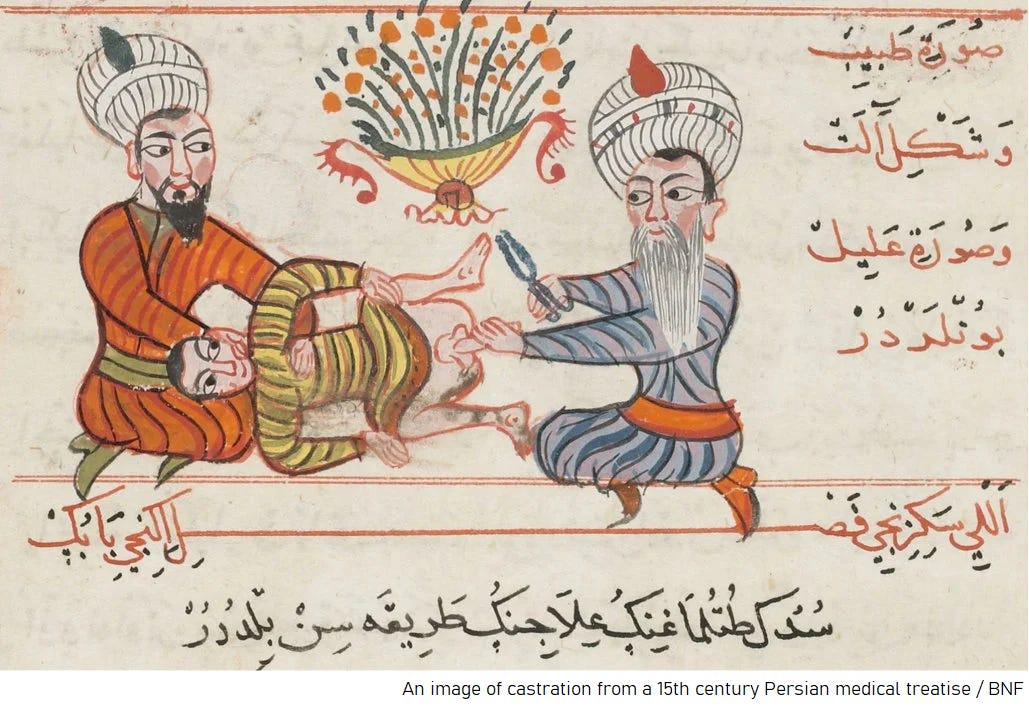

Male Castration

Castration, the removal of the testes via surgery, was from times immemorial the most common way to sterilize males. It involved risks of bleeding, infection, and permanent hormone irregularities for the patients who underwent it2 - but with rudimentary surgical knowledge, was for a long time the only way to sterilize humans.

Before the mid-nineteenth century, when anesthesia and antisepsis were introduced, any abdominal operation designed to sterilize a woman - such as ovariotomy (removal of the ovaries) or hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) - carried mortality rates so high that it was almost the equivalent of a death sentence. As surgical historians note, abdominal hysterectomy was “almost uniformly fatal” and ovariotomy “almost inevitably fatal,” and was therefore attempted only rarely by a few exceptional surgeons, usually in desperate emergencies rather than as a planned method of fertility control.3

Castration in History

In parts of West Africa, several kingdoms employed castration as a judicial sanction and also produced eunuchs for service within royal court structures.4 Although the practice may have originated as early as the sixth century before the common era, it became significantly more widespread during the medieval and early modern periods. Eunuchs formed an integral component of palace culture across both East and West Africa, in Muslim as well as animist polities.

Court eunuchs fulfilled a wide range of functions, most notably serving as gatekeepers, personal attendants to the ruler, guardians of royal harems, and supervisors of palace treasuries. In West Africa in particular, they frequently assumed military responsibilities as well. African eunuchs were also employed extensively in imperial courts beyond the African continent, especially in the Near East and South Asia. From the twelfth century onward, a corps composed largely of African eunuchs served as guardians of the Prophet Muhammad’s tomb in Medina and of the Kaʿba in Mecca.5

Within the broader Islamic world, including the Ottoman Empire, large numbers of enslaved African and other boys were castrated for service as eunuchs in courts and harems; a substantial proportion died during or soon after the procedure.

A parallel tradition existed in imperial China, where castration (gongxing) constituted one of the “Five Punishments” and could lead directly to service as a palace eunuch. Offenders subjected to this penalty had their genitals removed and were subsequently assigned to eunuch service within the imperial palace. Simultaneously, particularly during the Ming dynasty, castration also provided a pathway into palace employment for impoverished men who chose to self-castrate in hopes of securing a position when becoming a eunuch offered the sole avenue to relative privilege.6

Castration in Slave States

In several American colonies and slave states, slave codes prescribed castration as the statutory punishment for enslaved or Black men convicted of attempted rape of white women.7 Slave owners also at times resorted to castration extra-legally as a method of disciplining enslaved men they deemed unruly, with the aim of rendering them more compliant.

Legal historians note that castration functioned as a standard, codified penalty for enslaved men accused of sexual offences against white women. In effect, the deprivation of these men’s reproductive capacity became normalized within the legal culture of the United States.

Darwinism and Mendel’s Laws of Inheritance

Across the eighteenth century, the notion gained currency that criminal behavior was primarily hereditary.8

Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by means of natural selection profoundly reshaped contemporary understandings of both the natural world and human society. In 1864, the sociologist Herbert Spencer appropriated arguments from the first edition of “On the Origin of Species” and applied them to pre-existing racist and hierarchical interpretations of social life. Spencer coined the phrase “survival of the fittest,” which subsequently became one of the central tenets of social Darwinism after Darwin incorporated it into the 1869 fifth edition of “On the Origin of Species”.9 10 Social Darwinism emerged as a particularly influential framework in Britain, France, and the United States, where certain political and intellectual leaders promoted policies designed to allow the “fittest” to flourish while preventing the “masses” of the urban poor from doing so.11

Concurrently, in 1866, Johann Gregor Mendel demonstrated that specific traits - such as flower color - followed predictable patterns of inheritance based on the interaction of “dominant” and “recessive” factors.12 In subsequent decades, American eugenicists misapplied Mendelian principles to humans, asserting direct genetic causation for complex behavioral attributes such as intelligence and for purported hereditary predispositions to particular diseases. This interpretive framework came to be known as biological, or genetic, determinism.13

Notion of Hereditary Criminality and Imbecility

In a paper presented on February 11, 1879, to the Social Science Association of Indiana, Harriet M. Foster argued that “imbeciles” and the “feeble-minded” frequently inherited their condition. Foster stated that “intermarriage of consanguineous persons and the intemperance of one or both parents” were the most common causes of such mental impairments.14

Oscar C. McCulloch, a clergyman in Indianapolis, conducted a study of a group of families he labeled the “Tribe of Ishmael,” using records dating back to 1840. McCulloch claimed that his research demonstrated the hereditary transmission of “human degradation,” concluding that mental weakness, pauperism, licentiousness, and “poor morals” were hereditary in origin.15

Fallopian tubal litigation and Hysterectomy of Women

In 1880, Dr. Samuel Smith Lungren of Toledo, Ohio, performed what is generally regarded as the first modern fallopian tubal ligation.16 At this stage, the operation was undertaken on an individual, ostensibly therapeutic basis - primarily in life-threatening obstetric situations or in response to severe pelvic disease.17 Nonetheless, the demonstration that a woman’s fertility could be surgically terminated entered the medical repertoire and provided one of the technical preconditions for the later use of tubal ligation in eugenic and population-control programs. The so-called “Pomeroy technique,” a simple loop-and-resection method of tubal ligation associated with Ralph Hayward Pomeroy, was described in 1930 and over subsequent decades became the most commonly employed method of female surgical sterilization.18

Hysterectomy (removal of the uterus), which from antiquity through the nineteenth century had been a rare and extremely high-risk procedure, also came to be used widely in the early and mid-twentieth century as a de facto method of sterilization. Improvements in anesthesia, antisepsis, and abdominal surgery - building on the work of surgeons such as James Young Simpson and Thomas Spencer Wells in the nineteenth century, reduced operative mortality to a few per cent by the 1920s, after which hysterectomy was sometimes performed in a more radical fashion than strict medical necessity required.19

Birth of Eugenics as a movement

Sir Francis Galton, Charles Darwin’s cousin, coined the term “eugenics” from the Greek “eugenēs” (“well-born”) in his 1883 book “Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development”.20 Galton believed that the principles of mathematics and statistics could be applied to describe and predict the inheritance of specific traits - such as intelligence - from parents and even more distant relatives.

He advocated improving the human population through selective reproductive practices, beginning with what he called “positive eugenics,” the view that individuals of allegedly “superior” genetic stock should be encouraged to reproduce through financial and other incentives provided by the government.21

Neo-Malthusianism

Neo-Malthusianism, often described as a sibling movement to eugenics, emerged in Britain with the formation of the Malthusian League in London after Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant were prosecuted in 1877 for publishing a pro-contraceptive pamphlet.22 In his 1798 Essay on the Principle of Population, Thomas Robert Malthus argued that population tended to increase more rapidly than the food supply and therefore advocated “moral restraint” rather than artificial contraceptive methods.23 The Dutch Neo-Malthusian League later established what is generally regarded as the world’s first birth-control clinic in Amsterdam, whose success influenced subsequent international birth-control activism.

Both neo-Malthusians and eugenicists expressed anxieties about what they regarded as excessive numbers of births among the poor and the “unfit.” Neo-Malthusians focused primarily on limiting overall population growth, whereas eugenicists emphasized the supposed hereditary “quality” of the population. Many proponents in both movements shared the objective of reducing reproduction among those they classified as poor or “unfit”.24

Indiana’s School for Feeble-Minded Youth

In 1887, the Indiana General Assembly approved a bill establishing the Indiana School for Feeble-Minded Youth at Fort Wayne to serve as a state institution for “idiotic and feeble-minded” children. It created a sex-segregated institution for individuals labeled “feeble-minded,” the very population that would later become the primary target of sterilization laws. An act establishing a Board of State Charities was approved on February 28, 1889.

The Board’s first three secretaries helped to embed heredity as a central explanation for pauperism, crime, and mental deficiency in official state publications. During their tenures from 1889 to 1922, the Indiana Bulletin, published quarterly, regularly presented cases in which pauperism, criminality, and mental “defect” were attributed to hereditary causes.

Alexander Johnson, appointed the first secretary of the Board of State Charities in 1889, had been influenced by the work of Oscar McCulloch, who also assisted in Johnson’s appointment. In his memoirs, Johnson wrote: “Generation after generation, many of the families to which these defective people belonged had been paupers, in or out of the asylum; their total number and the proportion of feeble-minded among them steadily increasing as time went on.”25

In 1897, a law governing the care and control of orphaned, dependent, neglected, and abandoned children - granting the state and counties expanded authority to remove children from “unfit” homes and place them in institutions or with guardians - was adopted. Ernest Bicknell, Johnson’s successor, released an official report in 1896 lamenting the supposedly hereditary nature of pauperism. Amos Butler replaced Bicknell on January 1, 1898. Under Butler, the earliest known reference to sterilization as a means of preventing insanity and the reproduction of “defectives” appeared in an official state document.26

By this period, sterilization had begun to lose its earlier association with extreme punishment and was increasingly framed as a preventive measure aimed at the unborn offspring of individuals labeled “undesirable.”

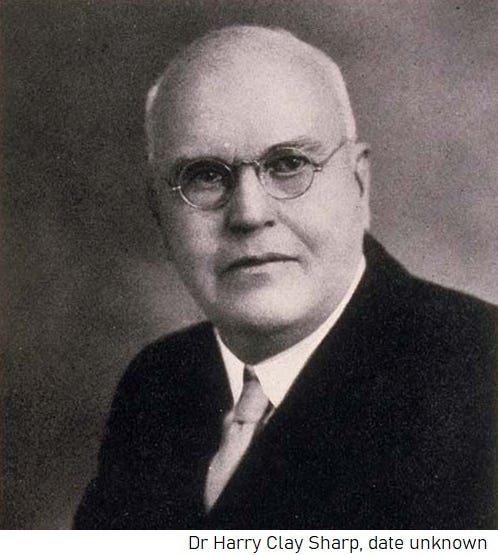

Vasectomy as “a more humane solution”

The vasectomy was developed in France, the United States, Sweden, and England beginning in 1857,27 initially as an experimental treatment for prostatic disease, particularly prostatitis.

The idea of employing the procedure for the purpose of sterilization - especially of those labeled “degenerate individuals” - as a purportedly more humane alternative to castration, because it preserved sexual functioning, was advanced by the Chicago physician Albert Ochsner. He published this argument in a 1899 article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, from which Harry Clay Sharp learned of the technique.28

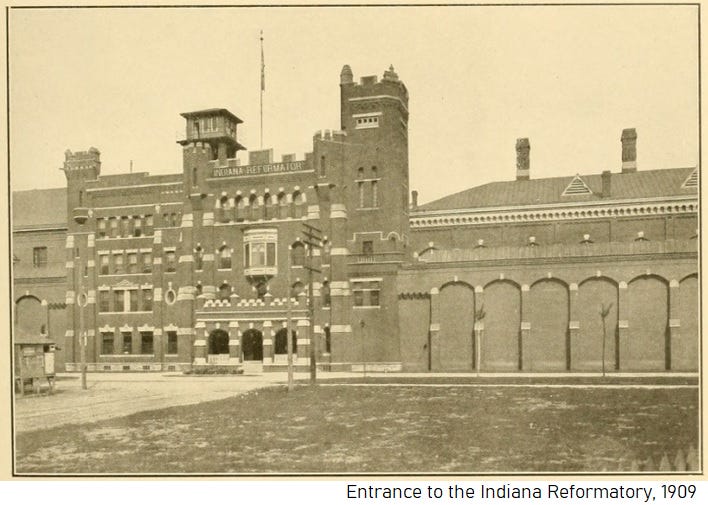

Sharp’s Initiatives and Experiments

Sharp, a surgeon, began working in 1895 as a physician at the Indiana Reformatory in Pendleton, Indiana, a state institution that housed convicted criminals and individuals classified at the time as “mental patients.”

Sharp reported that many inmates exhibited sexual behaviors he described as dysfunctional. In his writings on sterilization, he emphasized what he termed excessive masturbation and “spermatorrhea” - the involuntary emission of semen without orgasm - among male inmates. He claimed that these men experienced distress over their compulsive masturbation, which, he asserted, distracted them from their studies and daily routines, and that they approached him, as the institution’s physician, seeking treatment. These accounts, however, derive almost entirely from Sharp himself and were not corroborated by the prisoners.29

With the support of W. H. Whittaker, the superintendent of the Indiana Reformatory, Sharp performed his first vasectomy on October 11, 1899, on a nineteen-year-old inmate whom he said suffered from excessive masturbation. Sharp’s assertion that vasectomies could be performed relatively safely and at low cost provided rhetorical support to eugenics advocates - among them the National Christian League for the Promotion of Purity - which was seeking to secure passage of the first sterilization law.30

Mandatory Sterilizations in Indiana

On May 8, 1901, Governor Winfield Taylor Durbin approved a law supported by the Board of Charities that made unsupervised “feeble-minded” women aged sixteen to forty-five wards of the state, with the stated aim of preventing them from bearing additional children.31

Beginning in 1901, Sharp urged the governor’s office to enact a compulsory sterilization statute. He gained the support of Dr. John N. Hurty, Secretary of the State Board of Health, and together they examined why earlier efforts to mandate sterilization had failed.

As part of a renewed attempt to restrict the reproduction of those labeled “feeble-minded,” Durbin’s successor, Governor J. Frank Hanly - a prominent temperance and anti-vice reformer - approved a marriage law on March 9, 1905, that prohibited the issuance of marriage licenses to “imbeciles,” epileptics, and persons judged to be of unsound mind.

By 1907, Sharp succeeded in convincing Governor Hanly to approve the first compulsory sterilization law in the United States.32 In the years that followed, a number of other states enacted similar laws, sometimes in consultation with Sharp.33 Women were also sterilized on the grounds that they were “feeble-minded” or “promiscuous.”34

Sharp left his position at the Indiana Reformatory at the end of 1908 to open a private hospital, after performing 450 vasectomies on inmates; another physician succeeded him.35 In 1913, an inmate at the Reformatory, Eddie Millard - imprisoned for larceny - filed a complaint with the governor’s office alleging that Sharp had forced him to undergo a vasectomy. The complaint had no effect, as compulsory sterilization was legal under Indiana’s 1907 statute.

In Indiana, 2,424 people were sterilized. There was near parity by sex: 1,167 males and 1,257 females.36 Similar laws were enacted not only in numerous U.S. states but also in Canada, Scandinavia, Switzerland, Germany, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland.

In practice, a disproportionate number of eugenic sterilizations were performed in the U.S. on women, partly because pregnancy made alleged “defectiveness” more visible and because women were viewed as the primary conduit for future generations. By 1961, 61 percent of the 62,162 recorded eugenic sterilizations in the United States had been performed on women, and from the 1930s through the 1960s, far more institutionalized women than men were subjected to sterilization.37

Racial Hygiene in Germany

In 1904, the German biologist Alfred Ploetz founded the Archiv für Rassen- und Gesellschaftsbiologie (“Archive for Racial and Social Biology”), the first journal devoted primarily to racial hygiene and eugenics. The journal promoted concepts of Nordic and Aryan racial superiority.

From this initiative emerged the Society for Racial Hygiene, founded in Germany in 1905, which became one of the earliest organizations explicitly dedicated to eugenics. Other similar institutions, such as the Galton Institute in the United Kingdom, were established during the same period.38

Davenport & the American Breeders’ Association’s Committee on Eugenics

Charles Davenport - one of the leading early-twentieth-century American eugenicists who misapplied Mendelian principles to human heredity - was a Harvard-trained biologist who became a central figure in the U.S. eugenics movement. Davenport espoused openly racist views and argued that complex traits, such as intelligence, were determined by strict hereditary mechanisms.

In 1906, the American Breeders’ Association established a Committee on Eugenics, on which Davenport played a prominent role. The committee provided him with an institutional forum for promoting his eugenic program of selective and restrictive human breeding.39

Eugenics Record Office

In 1910, the Carnegie Institution of Washington, the philanthropist Mary Williamson Harriman, and the cereal manufacturer John Harvey Kellogg, with the support of Charles Davenport, established the Eugenics Record Office, which was placed under the direction of Harry H. Laughlin.40 Laughlin soon became a prominent advocate of eugenics, lobbying for legislation to restrict immigration and to authorize the sterilization of those labeled “defective.” Although the Station for Experimental Evolution initially declared its purpose to be the study of Mendelian inheritance patterns and animal breeding, the Eugenics Record Office focused in practice on human heredity and eugenics.

The Eugenics Record Office distributed questionnaires to families, constructed pedigree charts, and trained fieldworkers who traveled across the country to compile data on traits such as “feeble-mindedness,” “criminality,” and “alcoholism.” The office amassed records on thousands of families and sought to educate the public about the purported value of eugenics. Its publication, Eugenical News, was distributed nationally to promote eugenics research on fertility and related subjects.

In 1913, the recently incorporated Rockefeller Foundation, founded by John D. Rockefeller, began contributing funds to support the Eugenics Record Office.

The Bureau of Social Hygiene

In the United States and abroad, Rockefeller also funded the Bureau of Social Hygiene, which investigated prostitution, crime, and “delinquency” and supported birth-control and sex-education initiatives.

Rockefeller conceived the idea for the Bureau of Social Hygiene after serving on a grand jury in 1910 that investigated “white slavery,” the period’s term for forced prostitution.41 Frustrated with short-term public commissions that could only issue recommendations, Rockefeller created a private institution that he believed could address what he regarded as the era’s most pressing social problems. These included prostitution, political corruption, drug use, and “juvenile delinquency.”42 As one contemporary comment of Rockefeller puts it, whereas temporary public commissions “faded away,” a private bureau could shape policy and public opinion over decades.43

In 1912, the Bureau established the Laboratory of Social Hygiene at the Bedford Hills Women’s Reformatory. The Laboratory operated from 1912 to 1918, conducting examinations of female inmates for venereal diseases and performing physiological and psychological assessments aimed at defining a putative physical profile of the “criminal type.” After three years, it added a hospital for “mentally delinquent women” and sought to identify “inherited dispositions” toward mental illness and temperaments thought to predispose individuals to crime or sexual “promiscuity.”44 By 1915, the Laboratory explicitly attempted to detect hereditary predispositions to mental illness and “delinquent” behavior, thereby linking social hygiene, criminology, and eugenic theories of heredity.

Under Katharine Bement Davis, who became General Secretary in 1917, the Bureau expanded its focus from policing vice to conducting systematic research on sexuality.45 Her lobbying produced a collaboration with the U.S. National Research Council: the Committee for Research in the Problems of Sex (CRPS), launched in 1921. The CRPS became a central institutional channel for early sex research and later helped support Alfred Kinsey’s work through Rockefeller funding.

The Committee also later provided funding to Margaret Sanger’s American Birth Control League, founded in 1921, the organization that eventually became Planned Parenthood.

First International Eugenics Congress takes place

The First International Eugenics Congress, organized by the British Eugenics Education Society, was held in London in 1912. Leonard Darwin, son of Charles Darwin, presided over the event.46 About four hundred people attended, including Winston Churchill, Arthur Balfour, and Alexander Graham Bell.

Charles Davenport, the statistician Raymond Pearl, and the eugenicists Bleecker van Wagenen and Reginald Punnett were also present. Van Wagenen later presented a report to the Congress summarizing recent American sterilization laws and proposals to “sterilize the unfit.”

Kansas and the first “Fitter Family Contest”

Where there were individuals classified as “unfit,” there were also those designated the “fittest.” The Fitter Families for Future Firesides program - commonly known as the Fitter Family Contests - developed out of the earlier Better Baby Contests. These competitions began at the Kansas State Fair in 1908 and, under the sponsorship of the Eugenics Record Office, were soon replicated at state fairs across the country through the 1920s.

Participating families were required to submit detailed records of hereditary traits. Physicians at the events conducted physiological and psychological examinations of family members in order to assess their overall “eugenical worth.” Judges evaluated children aged six to forty-eight months on their physical appearance and supposed “mental capacity.” The winning families were almost invariably white.47

Global Expansion of Eugenics organizations

Developments in heredity theory, combined with the upheaval of World War I, contributed to a renewed interest in using eugenics as a tool for social improvement.

By the end of the war, eugenics organizations had been founded in Hungary, France, Italy, Argentina, Mexico, and Czechoslovakia. Although each reflected its own national context, these groups generally promoted racial ideologies that positioned white Anglo-Saxons as a “superior” race.48

In 1921, the American Museum of Natural History in New York City hosted the Second International Eugenics Congress, presided over by Henry Fairfield Osborn, the Museum’s president. Among the speakers was Harry H. Laughlin, who argued that European immigrants were inferior and that their birthrates posed a threat to what eugenicists termed the Nordic race.49

American Eugenics Society

The American Eugenics Society was formed in 1926 out of a committee established after the Second International Eugenics Congress in New York. Its founders included Harry H. Laughlin, Madison Grant - author of “The Passing of the Great Race”, a work later admired by Adolf Hitler - Irving Fisher, and several other prominent eugenicists.

The Society succeeded the Eugenics Record Office in sponsoring the Fitter Family contests and, from 1939, in serving as the primary institutional base for Eugenical News. At its height, it had more than 1,200 members, including Margaret Sanger.50

American Birth Control League

Margaret Sanger’s American Birth Control League became a key conduit between early twentieth-century eugenic theory and the popular birth-control movement.51

Through conferences on “Medical and Eugenic Aspects of Birth Control,” eugenics-inflected works such as “The Pivot of Civilization”52 and “The Eugenic Value of Birth Control Propaganda,”53 and a board that included leading eugenicists, the League explicitly framed contraception as a tool for reducing births among those classified as “unfit.”

Kaiser Willem Institute of Anthropology, Human Genetics, and Eugenics

Eugenics was gaining momentum in Germany, supported in part by American institutions. In 1927, the Rockefeller Foundation provided funds for the construction of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Genetics, and Eugenics in Berlin. Its director, Eugen Fischer, collaborated with Charles Davenport in the management of the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations. On the occasion of the International Eugenics Congress held in Rome in 1929, they drafted a memorandum to Mussolini encouraging him to advance eugenic policies with “maximum speed.” In 1936, Harry Laughlin’s “contributions to race hygiene in Germany” were recognized with an honorary degree from the University of Heidelberg.54

Between 1925 and 1935, the Rockefeller Foundation spent nearly three million dollars supporting German eugenicists and related institutes in psychiatry and “racial hygiene.”

Raymond Pearl’s Critique

In 1927, Raymond Pearl, one of the prominent American eugenicists, became an open critic of the movement, denouncing eugenics as having “largely become a mingled mess of ill-grounded and uncritical sociology, economics, anthropology, and politics, full of emotional appeals to class and race prejudices, solemnly put forth as science, and unfortunately accepted as such by the general public.”55

Pearl argued that eugenicists were guilty of hasty generalizations and propagandistic tendencies and that they used statistics poorly in order to dress up social prejudices as biology.

He was not alone. Several prominent geneticists and biologists - many of them former supporters of eugenics - developed similar criticisms, including Herbert S. Jennings, Edwin G. Conklin, William Bateson, and Thomas Hunt Morgan.

Nazi Germany and Eugenics Public Discredit

German eugenics took a markedly different and far more violent direction after 1933. Prior to the First World War, Germany’s racial hygiene movement shared many assumptions with eugenics programs in Britain and the United States.56 After the war, however, the German eugenics community radicalized. The enormous loss of life on the front and the severe economic crises that followed intensified concerns about the nation’s biological and financial future.57 These circumstances sharpened distinctions between individuals regarded as hereditarily “valuable” and those labeled “unproductive.” Commentators argued that many of the supposedly “valuable” had perished in battle, while people deemed “unproductive” - often those institutionalized in hospitals, asylums, prisons, or welfare facilities - had survived. Such claims resurfaced repeatedly during the Weimar Republic and into the early years of National Socialism, where they were invoked to justify compulsory sterilization and reductions in social support for disabled or institutionalized populations.

By the time the Nazis came to power, racial hygiene had become a significant part of both professional discourse and popular thinking. These ideas strongly informed Adolf Hitler’s worldview and that of other leading Nazis, who fused eugenic concepts with racial antisemitism to create an ideological framework for radical social engineering. With this combination, the regime established the political and intellectual conditions necessary to enact increasingly coercive measures in the name of “hereditary health.”

Racial hygiene played a central role in shaping many of the regime’s racial policies. Physicians, geneticists, and other medical professionals were deeply involved in identifying and targeting individuals whom the state defined as “hereditarily ill” - a broad category encompassing a range of mental, physical, and social disabilities. The Nazi state portrayed these individuals as both a biological threat to the nation’s future and an economic burden on the welfare system.

This outlook culminated in direct intervention in the reproductive lives of those so classified. One of the regime’s earliest actions in this area was the 1933 Law for the Prevention of Offspring with Hereditary Diseases, which mandated compulsory sterilization for people diagnosed with a range of disorders, including schizophrenia and so-called “hereditary feeble-mindedness.” Under this law, roughly 400,000 individuals were sterilized. The state expanded these policies with the 1935 Law for the Protection of the Hereditary Health of the German People, a marriage law that barred individuals deemed to possess “inferior” or “dangerous” hereditary traits from marrying partners considered genetically “healthy.” Together, these measures formed the core of the regime’s early eugenic program.58

Loss of Public Favor & Funding

Throughout the 1930s, eugenics continued to decline in credibility among both the public and the scientific community. Americans increasingly learned how scientists and officials in Nazi Germany promoted and implemented coercive eugenic policies - particularly the compulsory sterilization of individuals classified as “hereditarily ill” - and that some of these measures had been influenced by earlier sterilization laws in several U.S. states.

Concern about the scientific foundations of the movement also grew. In 1935, the Carnegie Institution convened a committee to evaluate the validity of eugenics research. Four years later, in 1939, Vannevar Bush, then president of the Carnegie Institution, terminated funding for the Eugenics Record Office, which subsequently closed.59 60

Japan’s Sterilization Programs

Japan, one of Germany’s allies, developed its own eugenic programs and research initiatives.

As early as 1915, the Japanese government created a leprosy (Hansen’s disease) control system based on segregation and reproductive regulation. Patients were rounded up and placed in leprosy sanatoria, where they were subjected to long-term isolation. Beginning around 1915, patients in these institutions were sterilized, and women were compelled to undergo abortions, practices justified by the erroneous belief that susceptibility to leprosy was hereditary.61

In 1940, the Konoe government enacted the National Eugenic Law (Kokumin Yūsei Hō), following the rejection of an even more severe draft known as the Race Eugenic Protection Law. The law also applied to colonial Taiwan and colonial Korea, including facilities such as the Sorokdo leper colony. Survivors from Sorokdo recall that, as in Japanese mainland sanatoria, patients were subjected to forced sterilization under colonial administrators.62

The National Eugenic Law formally limited compulsory sterilization to individuals diagnosed with “inherited mental disease,” encouraged genetic screening, and restricted access to birth control in order to promote reproduction among those considered “fit.” Historian Matsubara Yōko estimates that 454 people were sterilized under this law between 1940 and 1945.

Following Japan’s defeat, the Eugenic Protection Law of 1948 authorized “eugenic operations” and abortions to prevent the birth of “inferior offspring.” Between 1948 and 1996, approximately 25,000 people were sterilized, including roughly 16,500 who underwent the procedure without consent. Many were disabled or institutionalized individuals, as well as leprosy patients.63

Czechoslovakia’s Sterilization of Roma women

After the Second World War, almost the entire pre-war Roma and Sinti population of the Czech lands had been murdered; most Roma living there after 1945 were new arrivals, especially from Slovakia. Communist policy treated Roma not as a national minority, but as a “socially backward” segment of the population to be assimilated. The 1958 Act on the permanent settlement of nomadic persons forced the remaining nomadic Roma, particularly Vlach Roma, to settle; nomadism was banned, Roma cultural institutions were discouraged, and state policy increasingly aimed at demolishing Roma settlements and dispersing their inhabitants.64

During the post-1968 “Normalization” period, Roma were increasingly framed as a social problem, marked by allegedly high fertility, to be addressed through social engineering rather than recognized as an ethnic group with collective rights.65 From the 1970s to the late 1980s, Communist Czechoslovakia implemented a de facto sterilization policy aimed at reducing Roma birth rates. On the basis of a 1972 health ministry sterilization directive and later implementing measures, social workers and doctors systematically targeted Romani women with financial incentives, welfare pressure and, in many cases, operations performed without full, informed consent.66 Although Roma formed only a small proportion of the overall population, Romani women came to constitute a disproportionately large share of all women sterilized, making the program one of the clearest examples of racialized population control in late socialist Eastern Europe.67

Re-branding as “Neo-Malthusians”

Eugenics did not disappear when the atrocities committed by Nazi Germany and its allies were exposed. Instead, it adapted. Many eugenicists re-branded their ideas within the more publicly acceptable framework of neo-Malthusianism, which argued that population growth had to be controlled to prevent mass starvation and social collapse.

This re-branding occurred by abandoning the term “eugenics” and relabeling their work as population and family planning, social biology, or human genetics. The underlying concerns remained the same - questions about who should have children and how many, and anxieties over “quality” versus “quantity” - but these were re-framed as issues of economic development, environmental sustainability, or public health rather than racial science.

Fairfield Osborn’s “Our Plundered Planet”,68 and William Vogt’s “Road to Survival”69 helped launch a renewed environmental neo-Malthusian movement: in this revival, overpopulation was presented as a threat to natural resources and ecosystems, not only to wages or living standards.

“United” Nations & Population Council

The United Nations was formally established on 24 October 1945, when the UN Charter entered into force following ratification by the five permanent members of the Security Council and a majority of the other signatories.70

In the early post-war years, a Population Division was created within the UN Secretariat (then located in the Department of Social Affairs, now part of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs) to collect demographic data and analyse “population problems.” It began producing global population estimates and, in 1951, issued the first set of what would become the World Population Prospects series.71

In parallel, the Population Council was incorporated in New York on 7 November 1952 by John D. Rockefeller III, following a 1952 Williamsburg conference on the “population problem.”72 From the outset, Rockefeller and other founders framed rapid population growth in the “underdeveloped” or newly decolonized world as a potential threat to economic progress and political stability - a classic neo-Malthusian concern.

The Council’s mission was to address the perceived dangers of overpopulation in “underdeveloped countries” by promoting smaller families through contraception and related measures. It quickly became one of the most influential private actors behind the global population-control agenda of the 1950s-1970s and played a substantial role in shaping UN and governmental population programs, especially in Asia, Latin America and Africa.

Frederick Osborn, an early leading figure in the Population Council (and cousin of conservationist Fairfield Osborn), argued that “eugenic goals are most likely to be attained under a name other than eugenics.”73 He characterized birth control and abortion as “great eugenic advances,” but insisted that they should be defended in terms of health, freedom and development rather than under an explicit eugenics label.

In 1953, the UN published The Determinants and Consequences of Population Trends, a major report that analysed the relationships between demographic change and economic development.74 While cautious in tone, it treated rapid population growth - particularly in poorer countries - as a potential constraint on development and suggested that governments might consider fertility-reduction policies among the instruments of economic planning.

Through the early 1960s, the Population Division expanded its collection of demographic data and projections, which became the standard reference for global population debates. UN reports and conferences increasingly cast high population growth in newly decolonized countries as a development challenge, reinforcing a neo-Malthusian view that “overpopulation” hindered progress. In response to growing concern about demographic change and the spread of new family-planning technologies, the UN created, in 1967, the United Nations Trust Fund for Population Activities. This trust fund was soon upgraded into the United Nations Fund for Population Activities, later renamed the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), which became the central UN agency for population and reproductive-health programs.75

Council on Foreign Relations (CFR)

Established in 1921, the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is the leading U.S. foreign-policy think tank, and its journal Foreign Affairs serves as a primary forum for elite policy debate.76

From the 1960s onward, Foreign Affairs and CFR circles increasingly discussed the “population explosion” as a strategic issue, alongside decolonization and Cold War geopolitics.77 Many key actors in the population-control movement were CFR members or closely tied to its networks, including Henry Kissinger, John D. Rockefeller III, and McGeorge Bundy, who later became president of the Ford Foundation.78

Historical reconstructions of U.S. population policy during the 1960s and 1970s show that elite advisory communities - such as the CFR, major foundations, and leading demographers - advanced the view that the United States required a global population policy as part of its foreign-policy and development-aid strategies.79

The influential National Security Study Memorandum 200 (NSSM-200, 1974 - the “Kissinger Report”80), which remains official U.S. policy,81 argued that rapid population growth in selected “less developed countries” endangered U.S. security and access to strategic resources. It called for comprehensive family-planning programs in those countries. The document reflects the neo-Malthusian consensus prevalent in CFR-adjacent elite networks: population growth abroad was seen as generating political instability and resource competition, which in turn required management through contraception, incentives, and occasionally coercive measures funded through development assistance.

Limits to Growth & Club of Rome

The 1960s saw the rise of a modern “overpopulation panic,” brought to a wide public audience by Stanford’s Paul & Anne Ehrlich’s “The Population Bomb” (196882) and, a few years later, by “The Limits to Growth” (197283), the Club of Rome’s commissioned report authored by Donella Meadows, Dennis Meadows, and colleagues. Both works were explicitly neo-Malthusian: they largely abandoned earlier hereditarian language but continued to frame rapid population growth as a primary driver of resource depletion and ecological crisis.

The Club of Rome, founded in 1968 as an international association of industrialists, scientists, and public officials concerned with “the predicament of mankind,” commissioned The Limits to Growth to model long-term interactions between population, industrial output, food production, pollution, and non-renewable resources. The report argued that the earth’s “interlocking resources” could not sustain prevailing rates of economic and population growth much beyond the year 2100, and recommended stabilizing both population and industrial output at “sustainable” levels.

These analyses fed into and resonated with early United Nations debates on environment and population in the 1970s, including the 1974 World Population Conference in Bucharest,84 and reinforced a broader “overpopulation” discourse in policy circles of the Global North. In this climate, they were often cited - or at least echoed - as part of the rationale for increasingly assertive fertility-reduction programs in parts of the Global South.85

The combination of neo-Malthusian resource-limit thinking promoted by the Club of Rome and the security-and-development framing advanced in elite forums such as the Council on Foreign Relations gave post-war population-control agendas - including, in some countries, coercive sterilization campaigns - a sense of urgency and intellectual legitimacy, even as concrete interventions were implemented by states, aid agencies, and organisations such as UNFPA, USAID, the World Bank, and the Population Council.

Mass Sterilization of Native American Women in the United States

Throughout the late 1960s and 1970s, the United States witnessed a largely hidden but widespread pattern of involuntary sterilization of Native American women, carried out primarily through the federally administered Indian Health Service (IHS).86 This phenomenon emerged at the intersection of long-standing colonial medical paternalism, mid-century eugenic legacies, and the neo-Malthusian population-control climate that intensified across U.S. policy and philanthropic networks during the same period. Although the United States publicly distanced itself from explicit eugenics after the Second World War, the sterilization of Indigenous women demonstrates that coercive reproductive governance persisted within federal institutions well into the late twentieth century.87

Contemporary investigations, congressional hearings, and survivor testimonies indicate that thousands of Native American women - disproportionately young, economically disadvantaged, and often already mothers of several children - were sterilized through coercion, misinformation, or the complete absence of consent. Estimates vary, but several studies conclude that between 25 and 50 percent of Native American women of childbearing age were sterilized in certain IHS service regions between the late 1960s and early 1980s, with some estimates suggesting as many as 70,000 women.88 89

The mechanisms of coercion varied. Women frequently reported that consent forms were presented only in English, often during labor, under sedation, or immediately after childbirth, when meaningful comprehension was impossible. Others were told that sterilization was reversible, that their existing number of children jeopardized their access to welfare benefits, or that refusal could compromise future medical care. Some procedures were performed during unrelated surgeries, such as appendectomies or cesarean sections, without any prior discussion. Testimony collected in subsequent inquiries shows that many did not learn they had been sterilized until years later, after unsuccessfully attempting to conceive again.90

India’s state of Emergency

During the national Emergency of 1975-77, the government under Indira Gandhi, with her son Sanjay Gandhi playing a leading role, used police, local officials, and stringent numerical quotas to promote mass sterilization, overwhelmingly of poor men.91 Over the Emergency period, more than ten million people were sterilized; more than eight million procedures were carried out in 1976-77 alone, many within just a few months, and contemporary inquiries together with later research leave little doubt that a large share were performed under explicit coercion or threat.92

After the Emergency, the state publicly renounced compulsion but quietly shifted to a predominantly female-centered program of tubal ligation, implemented through target-driven sterilization camps and postpartum procedures in public hospitals. By the 2000s, female sterilization accounted for roughly three-quarters of contraceptive use. Documentation by Indian activists, Human Rights Watch, and others shows that many women - often young, poor, and recently postpartum - underwent sterilizations in unsafe camp conditions, with minimal counselling and no meaningful informed consent, resulting in hundreds of deaths as well as long-term complications.

Public interest litigation in the Supreme Court, including “Ramakant Rai v. Union of India”93 and “Devika Biswas v. Union of India”,94 and subsequent government reports formally acknowledged these abuses and ordered an end to mass sterilization camps. Nevertheless, recent studies and court cases indicate that coercive or non-consensual female sterilization remains a recurring feature of India’s family-planning system.95

Gursaran Talwar’s Research

In India, fertility-control research has not been limited to surgical methods.

Gursaran Talwar is an Indian-born immunologist. He was educated at the University of the Punjab, where he received his B.Sc. and M.Sc., and subsequently trained at the Pasteur Institute in Paris under a scholarship program.96 After returning to India, he founded the National Institute of Immunology (NII) in New Delhi, where he became known for his work in immunology and the development of “immunocontraception.”97

From 1972 to 1991, Talwar directed the ICMR-WHO Research and Training Centre in Immunology for India and Southeast Asia, an officially designated WHO-ICMR collaborative center. In 1972, he began developing the idea of creating an immunological method of birth control by designing a vaccine targeting human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), the hormone produced by the early embryo that is essential for implantation and the maintenance of pregnancy. Because hCG is a highly specific marker of early pregnancy and is indispensable for embryo implantation, Talwar reasoned that a vaccine inducing antibodies that neutralized hCG could block implantation and thereby prevent pregnancy.98

In a neo-Malthusian framework, this approach had appeal as a technocratic method to reduce fertility in high-growth populations - a strategy that appeared less politically volatile than mass sterilization campaigns while serving similar policy goals.99

Beginning in 1977, Talwar’s research received support from multiple international organisations, including the Population Council (via its International Committee on Contraception Research), the Ford Foundation, Canada’s International Development Research Center, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the WHO through its Task Force on Vaccines for Fertility Regulation.100 101 A contemporaneous Institute of Medicine report notes that the Population Council’s contraceptive research - immunocontraception included - was funded by the Ford, Rockefeller, and Mellon foundations, as well as by USAID and the U.S. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).102

In 1985, Talwar completed a postdoctoral fellowship at the U.S. National Institutes of Health under a Fogarty International Center program.103

After several unsuccessful early attempts,104 feasibility studies for an hCG-based contraceptive vaccine were completed and published in 1997 in the American Journal of Reproductive Immunology under the title “The HSD-hCG Vaccine Prevents Pregnancy in Women.”105 Talwar subsequently pursued Phase I clinical trials in India, Finland, Sweden, Chile, and Brazil.106

China-wide one-child policy

From the launch of the one-child policy in 1979 until its relaxation in 2015, China’s birth planning system relied heavily on sterilization. Demographic studies show that by the mid-1980s, intrauterine devices (IUDs) and sterilization accounted for around 80-85 percent of all contraceptive use, and by 1985 more than half of couples using contraception relied on sterilization.107 108

In 1983 alone, during a national “birth planning year,” approximately 16 million women and more than 4 million men were sterilized, alongside tens of millions of IUD insertions and induced abortions; by the end of that year, sterilization accounted for roughly half of all contraceptive practice in the country.109

Over the longer period 1980-2014, official figures indicate that about 108 million people were sterilized and 324 million women were fitted with IUDs.110

Although the 2001 Population and Family Planning Law formally prohibited compulsory abortion and sterilization, provincial regulations and local implementation continued to promote the principle of “IUD after first birth, sterilization after second birth,” often tying officials’ performance evaluations to the number of procedures carried out.111

Human rights organisations and UN bodies have repeatedly documented cases in which women - especially in rural areas - underwent sterilization under intense pressure, threats of fines or job loss, or outright coercion, making sterilization a central instrument of the one-child policy rather than a fully voluntary choice.

Late 1990s-2010s Namibia Sterilization of HIV Patients

From the late 1990s through at least the early 2010s, public hospitals in Namibia subjected a significant number of women living with HIV to sterilization without their informed consent. Most of these procedures were bilateral tubal ligations performed during caesarean sections in state facilities, with “consent” obtained through English-language forms presented to women in labor or under threats that they would be denied surgery or other essential treatment if they refused to sign.112

Community-based research conducted in 2008 among 230 women living with HIV documented more than forty cases of forced or coerced sterilization, and a 2010-2012 Harvard-Namibia Women’s Health Network study concluded that such practices were widespread and ongoing.113

In the landmark LM & Others v Government of Namibia case, the High Court in 2012 - and the Supreme Court in 2014 - held that three women had been sterilized without informed consent, affirming their rights to dignity, bodily integrity, and family life, although both courts declined to find explicit discrimination on the basis of HIV status.114

These litigated cases - representing only a small documented fraction of what evidence suggests was a broader, systemic pattern - exposed how poor HIV-positive women were implicitly treated as unfit to reproduce. They remain a key African example of how post-apartheid health systems can reproduce eugenic logic under the guise of clinical judgement and public-health management.

South Africa - “You HIV people must be closed up”

Since the late 1990s, poor Black South African women living with HIV have reported being sterilized in public hospitals without their informed consent. The procedures were typically bilateral tubal ligations performed during cesarean sections or shortly after delivery.115

Women reported being presented with consent forms while in labor, in severe pain, or already on the operating table, often in languages they did not fully understand.116 Many stated that they were told they would not receive the operation, antiretroviral therapy, or future care unless they signed. Others discovered that they had been sterilized only years later, when they tried to conceive again. South Africa has comparatively progressive legal protections: the 1996 Constitution and the 1998 Sterilization Act require informed consent and prohibit non-voluntary procedures.

In practice, however, implementation has been inconsistent, particularly in under-resourced public hospitals. A study conducted for Her Rights Initiative (HRI) documented dozens of such cases; 18 of the 22 women interviewed reported being coerced into signing consent forms. The 2015 South Africa HIV Stigma Index found that approximately 7.6 percent of HIV-positive women surveyed - about 500 respondents - reported having been forcibly sterilized.117

These complaints prompted the Commission for Gender Equality (CGE) to open a formal investigation, whose findings were released publicly in February 2020. The CGE’s report confirmed that women living with HIV in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal had been subjected to forced or coerced sterilization in public hospitals and concluded that signatures obtained under these circumstances did not amount to informed consent, given the timing, pressure, and misinformation involved. Testimonies included statements from staff such as: “You HIV people do not ask questions when you make babies. Why are you asking questions now? You must be closed up because you HIV people like making babies and it annoys us. Just sign the forms so you can go to theatre.”

The CGE found that these practices violated rights to equality, dignity, bodily integrity, and freedom from cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment. UNAIDS and the South African National AIDS Council (SANAC) publicly acknowledged the findings and called for redress and systemic reform. HRI and allied organizations are advocating amendments to the Sterilisation Act and stronger safeguards, including cooling-off periods, improved consent procedures, and monitoring mechanisms. In 2025, Parliament’s Portfolio Committee on Health heard evidence that such practices have persisted for more than two decades and that most affected women have yet to receive compensation.118 A 2024 University of South Africa (UNISA) study likewise describes forced and coerced sterilization of HIV-positive women since at least 1997 as a systemic violation of reproductive rights.119

Chile’s Sterilizations of HIV Patients

In Chile, cases of forced and coerced sterilization have been documented among women living with HIV, particularly in public hospitals.120 The emblematic case is “Francisca” (F.S.), a rural woman who in 2002 gave birth to an HIV-negative baby by cesarean section (C-section) in a public hospital.121

Without telling her or asking for consent, the surgeon performed a tubal ligation during the operation, deciding that an HIV-positive woman should not have more children. Chilean law already required prior written informed consent for sterilization; Francisca signed nothing of the sort.

Her experience was not unique. In 2010, the Center for Reproductive Rights and the Chilean NGO Vivo Positivo published Dignity Denied, based on interviews with 27 HIV-positive women in five regions. The report found that sterilization without knowledge or consent, or under pressure, occurred often enough and across the country to be considered systematic, even if not mandated by written policy.

Women recounted being discouraged from pregnancy, misinformed about transmission risks, and in some cases sterilized during C-sections or other procedures without being told. In 2009, Francisca’s case was taken to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) as F.S. v. Chile, alleging violations of her rights to non-discrimination, bodily integrity, and family life.

After more than a decade, Chile reached a friendly settlement before the IACHR in August 2021, accepting international responsibility and promising reforms.122 On 26 May 2022, President Gabriel Boric issued a public apology to Francisca, acknowledging that her involuntary sterilization was a serious human rights violation and committing to guarantee reproductive autonomy for women living with HIV.

2000s-2010s Canada - ongoing Indigenous cases

Alberta and British Columbia repealed their formal Sexual Sterilization Acts in the early 1970s, but Indigenous women remained over-represented among those sterilized up to repeal.123

Modern testimonies and reviews show that, after the 1970s repeal, sterilizations did not stop; they reappeared as “routine” tubal ligations in public hospitals, often framed as normal postpartum care but carried out without free, informed consent - especially in the case of Indigenous women.124

The situation came to light in 2015, when several Indigenous women publicly alleged that they had been pressured or harassed into tubal ligations immediately after childbirth at Royal University Hospital in Saskatoon.

Saskatoon Health Region (SHR) responded with an internal policy review and then commissioned an external review by Métis scholars Yvonne Boyer and Judith Bartlett, focusing specifically on postpartum tubal ligations of Aboriginal women.

The Boyer-Bartlett report (2017) documented what was happening in the 2000s and early 2010s.125 The review was based on in-depth interviews with Indigenous women who had undergone tubal ligation after giving birth in Saskatoon hospitals, together with interviews with health-care providers and child-welfare officials.

Women consistently described being approached while in labor or immediately postpartum, often in severe pain, exhausted, or medicated; asked to sign forms, sometimes with little explanation; and told or strongly led to believe that they “had to” agree because of their life circumstances (poverty, addiction, number of children) or because Child and Family Services might apprehend their baby. Many did not understand that tubal ligation is permanent; they believed it was a reversible form of birth control.

The women depicted overarching themes of feeling invisible, profiled, and powerless; experiencing coercion; and suffering long-term impacts on self-image, relationships, and trust in the health-care system.

Testimonies of forced sterilizations appear as late as 2010.126 SHR’s own data, included in an appendix to the Boyer-Bartlett report, track inpatient postpartum tubal ligations at Royal University Hospital from 2010 to 2016 and show non-trivial numbers. Although the report does not provide a full ethnicity breakdown, the external review exists precisely because Indigenous women stated that their procedures in those years were not freely chosen.

Reports of abuses similar to those in Saskatoon are found across Canada.127 Federal briefing notes acknowledge at least six court cases (several of them class actions) alleging sterilization without proper consent from 1948 to the present, with Canada a defendant in most of them.128

China - Xinjiang (Uyghurs & other Muslim minorities)

Since the late 2010s, Xinjiang has shifted from relaxing birth limits - consistent with national trends - to adopting almost the opposite approach toward Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities. The region has implemented highly restrictive and often coercive birth-control measures, including IUD insertions, sterilizations, and “birth-violation” penalties, while the rest of China has moved into a pro-natalist phase.129

Prior to 2017, ethnic minorities in Xinjiang were permitted one more child than Han couples, often two or three children compared with one for urban Han households. In 2017, however, Xinjiang amended its regional regulations to “equalize” birth limits across ethnic groups and significantly strengthened enforcement.

Under the “Strike Hard” and “de-extremification” campaigns, authorities began to treat “having too many children” as a potential indicator of religious extremism or political disloyalty.130 A 2017 regional directive on reducing fertility rates set explicit targets for lowering birth rates by at least 4 per 1,000 compared with 2016, especially in predominantly Uyghur southern prefectures.131

During this period, Beijing was relaxing family-planning rules nationwide - the two-child policy was announced in 2015 and implemented in 2016, and the three-child policy was introduced in 2021132 - but Xinjiang adopted a markedly different trajectory for minorities, in effect a regional “reverse policy.”

Research by Adrian Zenz, ASPI, and others reconstructs this policy shift using Chinese government tenders, budgets, and statistical releases.133 Government documents show substantial increases in funding for “family-planning surgeries” and targeted birth-control campaigns in southern Xinjiang from about 2016 onward. By 2018, approximately 80 percent of all net IUD placements in China (insertions minus removals) occurred in Xinjiang, which has less than 2 percent of China’s population.

County-level documents describe free IUD insertions, tubal ligations, and other “birth-control surgeries” as priority tasks in rural Uyghur villages, often with quotas for women to be “rectified.”

Testimony from former detainees and local residents - corroborated where possible with official documents - reports forced IUD insertions prior to transfer to detention centers; coerced sterilizations presented as the only alternative to punishment; and unknown injections or pills given to women in custody that halted menstruation for prolonged periods.134

As a result, violations of family-planning policy became tied directly to the security and “stability maintenance” system. Local regulations list interference with or violation of family-planning policy implementation as a potential indicator of extremism, and county-level plans indicate that such violations may lead to referral to “vocational skills education and training centers” (VETCs). Some county plans instruct Uyghur villages to “eliminate illegal births” and raise IUD or sterilization coverage to near-universal levels among women of childbearing age with existing children.

Using official Chinese statistics, researchers have found that Xinjiang’s overall birth rate fell from 15.88 per 1,000 in 2017 to 8.14 per 1,000 in 2019 - a nearly 50 percent decline within two years, far steeper than national trends. In minority-dominated southern prefectures such as Hotan and Kashgar, the decline was even sharper: in Hotan, the birth rate fell from 20.94 per 1,000 in 2016 to 8.58 per 1,000 in 2018.

ASPI’s Family De-planning report estimates that, under current policy trajectories, between 2.6 and 4.5 million fewer births among Uyghurs and other indigenous minorities may occur between 2017 and 2040 than would otherwise be expected.

The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), in its 2022 report on Xinjiang, notes an “unusually sharp rise in sterilizations and IUD placements” compared with national trends, as well as a “steep decline in birth rates” in minority regions after 2017. The report concludes that these figures, in combination with credible testimonies of forced IUD insertions and sterilizations, indicate that coercive birth-control measures have been used against Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities.

The Chinese government strongly denies any coercion or targeted birth suppression. A 2021 white paper states that the Uyghur population grew from 10.17 million to 12.72 million between 2010 and 2018 and claims that minority populations grew faster than the Han population in Xinjiang.135 Official commentaries accuse researchers such as Zenz of “data abuse” and maintain that all family-planning measures are voluntary and aimed at balanced development.136

Critics respond that these cumulative figures end in 2018 - precisely when annual minority birth rates begin collapsing; that total population can continue to grow for a time even as annual births fall sharply due to cohort momentum; and that the central issue is not whether growth stops entirely, but whether birth rates are being deliberately and disproportionately suppressed among a protected group while the rest of China transitions toward pro-natalist policies.

Alleged use of Talwar’s “Vaccine against fertility” in Kenya

Kenya, like many African countries, conducted forced sterilizations of HIV patients.137 But the country’s recent history also exposed a concerning alarm of possible covert use of Talwar’s anti-fertility vaccine.

In 1995, a neonatal tetanus eradication campaign was planned in Kenya, backed by the World Health Organization (WHO), and targeting women aged 15 to 49 years - women of childbearing age. Dr. Stephen Karanja, an obstetrician, stated that “we were already giving tetanus injections to all pregnant women attending antenatal clinics to prevent neonatal tetanus. That was already part of the program in the country.” He added that the WHO insisted that vaccination should also be given “outside pregnancy.”

Aware of similar tetanus vaccine campaigns and concerned about possible risks to fertility, Dr. Karanja petitioned the Catholic Church, which runs a large network of health facilities in Kenya, to test the vaccine for β-hCG. Before testing could begin, however, the WHO withdrew the program. The campaign only received formal government backing in 2013, eighteen years later.

In 2014, Kenya’s Ministry of Health, together with WHO and UNICEF, launched a maternal and neonatal tetanus immunization campaign targeting girls and women of reproductive age (approximately 15-49), involving a series of five doses administered over time.138 The Kenya Conference of Catholic Bishops (KCCB) and the Kenya Catholic Doctors Association alleged that the government and WHO/UNICEF were covertly conducting a mass sterilization campaign by “lacing” the tetanus vaccine with β-hCG, the hormone used in experimental contraceptive vaccines.139 140 They stated that, in March 2014, three independent Nairobi-accredited laboratories detected β-hCG in vaccine samples,141 and that in October 2014 six further vials were tested in six laboratories, with β-hCG reportedly found in half of them.142 143

Dr. Muhame Ngare, then spokesman for the Kenya Catholic Doctors Association, argued that the campaign represented a “well-coordinated population control mass sterilization exercise using a proven fertility-regulating vaccine.” He further contended that the vaccination schedule - five doses spaced six months apart - was unexpected for tetanus control.144

On 12 November 2014, WHO and UNICEF issued a joint statement strongly denying the allegations. They asserted that the vaccines used were standard tetanus toxoid from WHO-pre-qualified manufacturers, tested under established global safety systems, and that no evidence supported the bishops’ claims. Kenyan authorities and WHO stated that their independent laboratory tests found no β-hCG, and that some of the vials provided by the Church were not from intact or verifiable cold-chain storage, raising questions about contamination.145

Following the public dispute, Parliament’s Health Committee requested joint testing of the vaccine, to be carried out by a team composed of Ministry of Health officials, Church representatives, academic experts, and AgriQ Quest Ltd., a Nairobi laboratory accredited by the Kenya National Accreditation Service. Both the Ministry and the Church agreed that AgriQ Quest should perform the laboratory analysis.146

Two categories of samples were tested. First were Church-supplied “field samples,” including some vials previously tested by smaller Nairobi laboratories. According to later accounts, including the 2017 article by Oller et al. and statements by opposition leader Raila Odinga and by the Catholic Health Commission, AgriQ Quest again detected β-hCG in several of these field samples. Second were vials supplied by the Ministry of Health from official government stores: approximately 50-52 vials, reported to be from the same batch numbers used in the campaign. AgriQ Quest’s tests on these samples did not detect β-hCG.

In 2017, a group including members of the Kenya Catholic Doctors Association and several U.S. co-authors published an article titled “HCG Found in WHO Tetanus Vaccine in Kenya Raises Concern in the Developing World,” claiming that ELISA testing showed β-hCG in some vials. The publication was targeted by substantial criticism.147 148

During the 2013-2015 period, Dr. Nicholas Muraguri served as Director of Medical Services and later as Principal Secretary for Health, acting as the Ministry’s spokesperson on vaccination and other health matters.149 According to later allegations, Dr. Muraguri asked AgriQ Quest to alter its results to state that the vaccines were safe for use. After the laboratory declined to modify its findings, WHO and the Ministry publicly rejected the Church’s claims and asserted that the vaccines were “absolutely safe” and free of β-hCG.

Government officials later argued that the Church’s samples may have been contaminated, while the Church argued that the hCG detected was in a chemically bonded form consistent with formulations used in research on fertility-regulating vaccines, and therefore could not have been introduced during handling.

In a documentary by Andrew Wakefield,150 unfortunately easy to criticize, due to its sensationalism and factual errors, by equally inaccurate “facts checks”,151 Frederick Muthuri further testified that the vials communicated by the government had been voluntarily mis-labeled - by hiding the original manufacturer information and batch numbers, to make them fit the batches collected by the church. Below is a five minutes excerpt of the documentary - focused on the essential witnesses testimonies for brevity.

The laboratory later threatened to sue the Kenyan government - and its official accreditation to carry such testings was withdrawn.152

Dr. Muraguri later became linked to a series of major procurement and governance controversies at the Ministry of Health, including the “Afya House” audit, the Managed Equipment Services (MES) leasing scheme, and the mobile-clinic procurement. Although he has not been convicted in court, parliamentary committees, journalists, auditors, and civil-society organizations have criticized his role, alleging obstruction of investigations, failure to provide key documents, and threats against reporters.153

An internal audit in 2016 flagged 5 billion Kenyan shillings in questionable expenditures. A Senate committee later described aspects of the MES project as a “criminal enterprise” and recommended investigations by the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission.

Conclusion

Across more than two millennia, efforts to control human reproduction have evolved from crude punitive practices to bureaucratic programs clothed in the language of science, development, and global governance. This historical survey has traced that evolution: from the physical mutilation of enslaved people, prisoners, and outcasts; through the rise of hereditarian science and state eugenics; into the internationalization of population control; and finally into the diverse modern forms of coercive or non-consensual sterilization that recur across continents.

Despite their differences in method, ideology, and institutional setting, these interventions are unified by a single underlying impulse: the belief that authorities - political, medical, or technocratic - can and should decide who is “fit” to reproduce.

While differing in intensity and intent, all share two consistent features:

the power asymmetry between those who decide and those subjected to the intervention, and the erosion of informed consent, often disguised as public health, welfare, or modernization.

The development of hCG-based fertility-regulating vaccines in the late twentieth century, for instance, illustrates how scientific innovation can align with longstanding neo-Malthusian goals. The global roll-out of genetic-therapy-based vaccines during the COVID-19 crisis similarly renewed the questions about trust, transparency, oversight, and the balance of power between pharmaceutical actors, governments, and the public. Although the scientific aims differ from past eugenics programs, the political conditions of authority - centralized expertise, emergency policy, and technological opacity - appears very close from the historical precedents we inventoried.

A society that does not understand the history of reproductive regulation is ill-equipped to evaluate the major ethical implications of modern bio-technologies.

💬 Join the conversation

Want to like, comment, or share this article?

Head over to our Substack page to engage with the community.

Likes, comments, and shares are synchronized here every 5 minutes.

https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/countries/2022-08-31/OHCHR-assessment-xinjiang.pdf

💬 Join the conversation

Want to like, comment, or share this article?

Head over to our Substack page to engage with the community.

Likes, comments, and shares are synchronized here every 5 minutes.